The Mni Wiconi Movement: A Look Back

One year ago, in February 2016, our families on Standing Rock started organizing with urgency, and a new community action collective, Chante Tin’sa Kinanzi Po (People, Stand with A Strong Heart) emerged. The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) was coming, despite more than two years of objections raised directly to the company, Energy Transfer Partners, and years of successive Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council resolutions passed in opposition to pipeline construction within the boundaries of our treaty lands—which extend far beyond the illegally reduced boundaries of our contemporary reservation. Dakota Territory once encompassed much of western modern day North and South Dakota. For millennia, innumerable generations of our ancestors have been born along our rivers and the delicate network of watersheds veining the vast prairie expanses of our homelands. Standing Rock spans the North and South Dakota border and is defined by rivers–the Cannon Ball on the north, the Missouri on the east, and is bisected by the Grand River, the birth and resting place of Sitting Bull.

In the midst of last winter’s subzero temperatures punctuated by youth basketball tournaments, open gym nights, and the occasional wacipi (powwow), young people throughout Standing Rock’s eight districts—covering 2.3 million acres—arrived at the realization that the federal and tribal bureaucracies and court systems would likely do nothing to stop pipeline construction from occurring directly underneath Standing Rock’s primary drinking water source, Mni Sose, the Missouri River—a once swirling and unpredictable presence, now swollen into a sprawling reservoir called Lake Oahe, spanning hundreds of miles between the capitol cities of Pierre, SD and Bismarck, ND.

A movement grounded in direct action, prayer, and ceremony was born. The young people of Standing Rock, Cheyenne River and our sister tribes among the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), or Great Sioux Nation, hit the ground running in March, to raise awareness about the imminent threat to so many communities’ drinking water. In the arid northern plains, water is precious and in constant motion. After torrential rains and the Wakinyan (Thunder Beings) announce the arrival of spring, droughts commonly ravage the region during summer months, abetted by seemingly endless winds and blazing sunshine.

“We need solar and wind power, not pipelines that threaten our water and fishing rights,” our youth proclaimed. Mentored by a group of young parents and community leaders like Honorata Defender (whose father led a pipeline resistance movement to the Northern Border natural gas line in the early 1980s), Jonathan Edwards, a paramedic, and Waniya Locke, a language teacher, and others, a small group of teens and twenty year-olds set about casting off the weight of apathy and foregone conclusions that entrench in impoverished reservation communities plagued by decades of health disparities, suicides, and drunk driving fatalities. (Corson County, SD, and Sioux County, ND, annually rank among the ten most economically depressed counties in the U.S.)

“Run for Your Life,” Standing Rock’s first public anti-pipeline prayer event crossed the two Missouri River bridges between the tiny reservation community of Wakpala, SD, and Mobridge, SD, on the east bank of the river. Several dozen participants appeared in support after a quick week of organizing and outreach, but few in Mobridge seemed to share the youth’s sense of urgency. Later, the Four Directions Walk, Run, March, and Ride was organized when the Army Corps of Engineers scheduled listening sessions on Standing Rock, and a tribal radio station volunteer from KLND 89.5, “Lodge of Good Voices,” showed up with his new drone to capture footage of the horseback riders, motorcyclists, youth runners, and march participants as they converged on the Grand River Casino at the confluence of the Grand and Missouri Rivers. Grandparents delivered impassioned and tearful lectures to a young Army colonel, recounting their parents’ loss of nearly two hundred thousand acres of the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Sioux Reservations’ best farmlands, gardens, orchards, and grazing acreages after the Corps’ 1958 damming of the Missouri River inundated hundreds’ of families households, annihilating local tribal food systems and economic independence.

“Never again,” they vowed. “Water is life. Mni Wiconi. This is all we have left—our river, and the lands you didn’t take last time.”

Even the smallest attendees understood the stakes: “We can’t have oil in water if we want to live,” a six-year old named Love told Army Corps staffers charged with assessing the viability of the Energy Transfer Partners permit application.

No one yet knew that it was the Corps who mandated a reroute of the proposed line from north of the Bismarck state capitol, to just a half mile from Standing Rock’s northern border—and just a few short miles from a main reservation drinking water intake. But certain that the Army Corps would continue to ignore their pleas to protect the drinking water needed for all the Sioux reservations’ communities (and agricultural production by Native and non-Native farmers and ranchers alike), tribal youth, grassroots and elected leaders launched a community horseback ride from the Standing Rock Tribal headquarters in Fort Yates, ND, on April 1, covering twenty-six miles to the tiny community of Cannon Ball, ND, which overlooks a beautiful meandering Cannon Ball and Missouri River flood plain nestled between steep ravines and high muddy river banks.

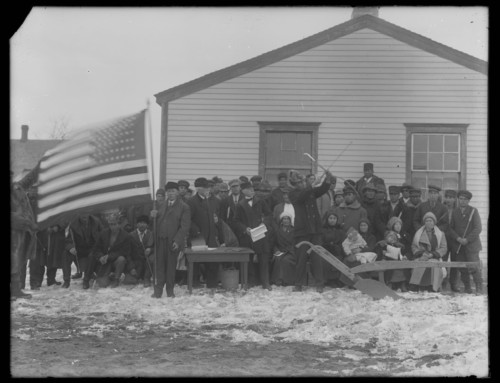

A grandmother and tribal historian, LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, whose family lands and cemetery abut the riverine zone, welcomed the riders to a wind-whipped pasture off a narrow dirt road off a bumpy gravel road, off a pitted asphalt road— just a few miles past the powwow grounds where President and First Lady Obama only eight months earlier had joined in the annual Cannon Ball Flag Day Wacipi (Celebration). Following the long Friday afternoon horseback ride, a few Cheyenne River citizens—fresh out of the KXL pipeline protest camp erected near the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in the proposed KXL path—pitched their tipis and never left. The encampment was named Sacred Stone, after the original Dakota name of the Cannon Ball River, where its whirling confluence with the Missouri tumbled boulders into perfect spheres revered in ceremonies for millennia by a half dozen tribes of the northern plains who utilized portions of the area for village encampments, ceremonial spaces, and burial grounds.

Driven to do still more to bring the region’s attention to the prospective pipeline’s potential for destruction, a handful of youth then found allies in some of Standing Rock’s local district governments—local tribal councils for each of eight reservation communities—and were soon successful in lobbying the Tribal Council to earmark funds to help them share their story online through video diaries and a new website (RezpectOurWater.com), to house their Change.org petition to the Army Corps. The young people got to work recording their love letters to the river, sharing them via their social media networks, and decided a few weeks later to set out on foot to deliver their petition signatures directly to the Army Corps Region 8 Headquarters in Omaha, NE.

Though every community event to that point had begun in prayer and had been led by family eagle staffs belonging to traditional headsmen and spiritual leaders, not all in the Sacred Stone Camp and the local districts were uniformly in support of such an ambitious youth effort that would take attention and resources away from the new prayer encampment. But the twenty-two year old mother, Bobbi Jean Three Legs from Wakpala, who’d organized the “Run for Your Life” in March, found unqualified support from Defender, Edwards, and Locke, and they promised vehicle support and inter-reservation coordinating. An uncle from the Taken Alive family held a blanket dance at a small local powwow, yielding a couple hundred dollars for the 700-mile journey south.

“Just go. Let the people know what’s happening, and they’ll join you. They’ll come to support us,” she recalls Edwards reassuring her the morning of April 22nd as he and his father and their dog Buddy drove her from Wakpala to Sacred Stone with a few cases of water and her duffle bag. They picked up a few friends along the way, met some elders at the camp, and all prayed together before setting off up the long winding hill out of Sacred Stone. Relay style, Three Legs and her friends ran the equivalent of three marathons that rainy Saturday, hopping in and out of the van and pickup truck escorting them. Doubt and uncertainty gripped them all morning as they slogged up and down the slick North Dakota highways, crossing the border into the southern half of Standing Rock. Just before they reached McLaughlin in Standing Rock’s Bear Soldier District, Three Legs recalls three horses galloping across a field to the fence line to jog along side them. She heard the sudden deafening crash of thunder, and “I knew the ancestors were with us. I knew we could do it.”

Through the subsequent journey south along the river and into Nebraska, the runners’ numbers ebbed and flowed. They stopped often to tell their story. Somewhere on Cheyenne River an elderly man stopped them to ask what they were doing, listened intently, and told them he’d tell his relatives and fellow Crazy Horse descendants to help them. Meanwhile, Locke and organizers from the Indigenous Environmental Network, helped arrange lodging and meals. Treaty council leaders, grandmothers, and families opened their homes, community centers, and their hearts to the runners’ journey for the water, and for the health of Mni Sose and the people.

In late July, the youth set off for Washington, D.C. armed with tens of thousands more signatures to rally at the national Army Corps Headquarters and the White House. When they returned home to Standing Rock in late August, they joined a movement transformed—a standoff along ND Highway 1806 as dozens of armed state and county law enforcement officers protected DAPL survey crews who had begun their destructive work. But now, the runners and citizens of Standing Rock were supported by hundreds, then thousands of campers who had overfilled the space available in Sacred Stone and taken up residence north of the Cannon Ball River on treaty land claimed by the Army Corps of Engineers. The seemingly impossible odds of teens and families on foot and horseback facing down a billion dollar industry with nothing more than prayer flags and sacred pipes, had also caught the attention of young Hollywood, and stars like Shailene Woodley and the cast of The Avengers amplified daily #rezpectourwater #nodapl and #mniwiconi #waterislife posts across social media platforms. Suddenly #standingrock was trending.

Indigenous Peoples and tribal delegations from across North and South America flocked to the encampments, which swelled into three main areas along the rivers—Sacred Stone, Oceti Sakowin, and Rosebud—and a row of flags grew to represent more than 300 tribal and international nations. Everyone had a story to share of struggles to protect precious homelands and waters from aggressive extractive industries, and songs and stories in dozens of languages hummed late into the summer, then fall, nights. Winter loomed, and the camps were abuzz in cold-weather preparations, all while the movement evolved into dramatic daily direct actions, with unarmed prayer marchers facing down an increasingly militarized police presence alongside armed DAPL security forces well equipped with all terrain vehicles, pickup trucks, helicopters, and surveillance planes that circled the encampments day and night, watching and counting. Mass arrest events mounted, drawing dozens then hundreds into a thicket of legal charges that quickly escalated from misdemeanors to felonies. More than 700 now face criminal penalties and jail time in North Dakota’s well-funded petro-state justice system, awash in oil and fracking industry lobbying contributions and tax revenues.

The Standing Rock youth’s Rezpect Our Water Change.org petition has since garnered 730,000 signatures, and local, independent and Indigenous media outlets have shared dramatic drone and live stream footage of more than 76 law enforcement agencies swarming into pastures astride armored military vehicles, armed with concussion grenades, water cannon, sound cannon, and other “less-lethal crowd control” weaponry deployed at point-blank range on teens and elders alike. Bones have been broken, horses put down from their injuries, but not a single arrestee has yet been charged with possession of a weapon.

As DAPL has returned to drilling, and projects completion of their river crossing within the month, the prayer camps are on the move—uphill out of the Cannon Ball and Missouri River spring flood zones. Spirits are unbroken, but tempered with bouts of grief and rage at the ongoing injustice of $33 million in state law enforcement costs arrayed against families and teens who only want to ensure clean water for present and future generations.

Across Standing Rock, young people pore over pipeline safety records and research solar and wind power production, while growing numbers of slender wind turbines and silvery solar panels glint in the late winter prairie sunlight. Spring is coming soon, but unusually, the Wakinyan (Thunder Beings) have kept watch all winter, appearing during the throes of the worst of the December blizzards. Along the frozen rivers, under the ever-brighter lights of DAPL construction crews, military veterans are arriving—frustrated by the months-long onslaught of Constitutional rights violations—and together with the youth and allies of Standing Rock and Cheyenne River, they keep vigil and remind one another: Chante Tin’sa Kinanzi Po (People, Stand with A Strong Heart)!

Jennifer Weston, Hunkpapa Lakota